The Riddler: dice rolling

Published:

Dungeons and Dragons is not just about rolling dice. It’s about collaborative storytelling, solving problems creatively, and exercising the imagination. The game has remained popular in the decades since its release for good reason, and during that time it’s compiled a large fan base (which includes some well-known figures).

To be fair, though, dice rolling is very much a big part of it. Most events that take place in the game are dictated by one or more rolls of dice of different varieties (none more iconic than the 20-sided die, or D20), as supervised by the Dungeon Master (DM) whose job it is to craft the imaginary universe the characters inhabit. The more difficult or unlikely the event, the higher the dice roll meeds to be. Want to jump across a narrow stream? Rolling a D20 for 5 or better would probably do it. Want to jump across raging rapids full of flesh-eating piranhas? Maybe to make it aross the target number to beat is 18.

Sometimes, a DM can reward you as a player for being creative. Say you decide to throw some food into the river to distract the piranhas. The DM can give you advantage on the river-jumping roll, meaning that you get to roll the D20 two times and pick the higher number of the two rolls to determine your success.

But the DM giveth, and the DM taketh away. She can also give you disadvantage, meaning that you roll twice and use the smaller of the two rolls. So if your character twisted their ankle earlier in the adventure, you might have disadvantage when trying to make the jump.

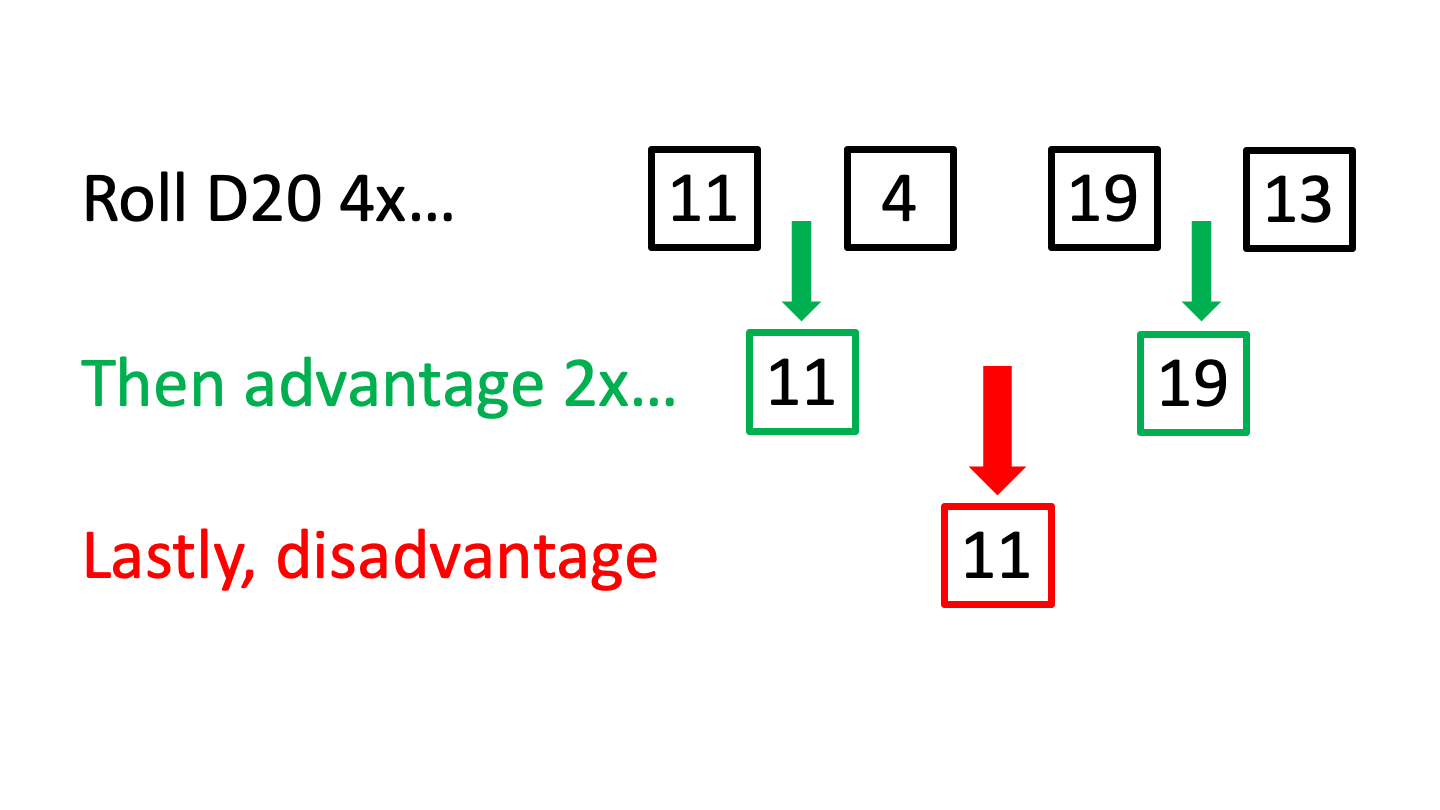

Last week’s Riddler Classic asks: what if we take the idea further and consider what disadvantage of advantage looks like? That means that you roll with advantage twice, and use the smaller of the two resulting numbers. Here is a diagram showing an example:

The black numbers correspond to the results of D20 rolls. For each pair of rolls, we take advantage by selecting the higher number to get two green numbers. Finally, we take disadvantage by using the smaller of the two green numbers to get to the final red number.

This brings us to the riddle. What is the expected roll you get with either disadvantage of advantage (which I will refer to as DisAdv form now on) or the analogously defined advantage of disadvantage (AdvDis)? And what is the probability of each approach beating a specific target number, \( N \)?

Solving these questions exactly can be done using the concepts of probability density distributions and cumulative density distributions. However this is a question about dice rolling, and I choose to solve it by rolling the metaphorical dice in my computer. Rolling millions of D20s is a simple way to solve the problem with a high degree of precision.

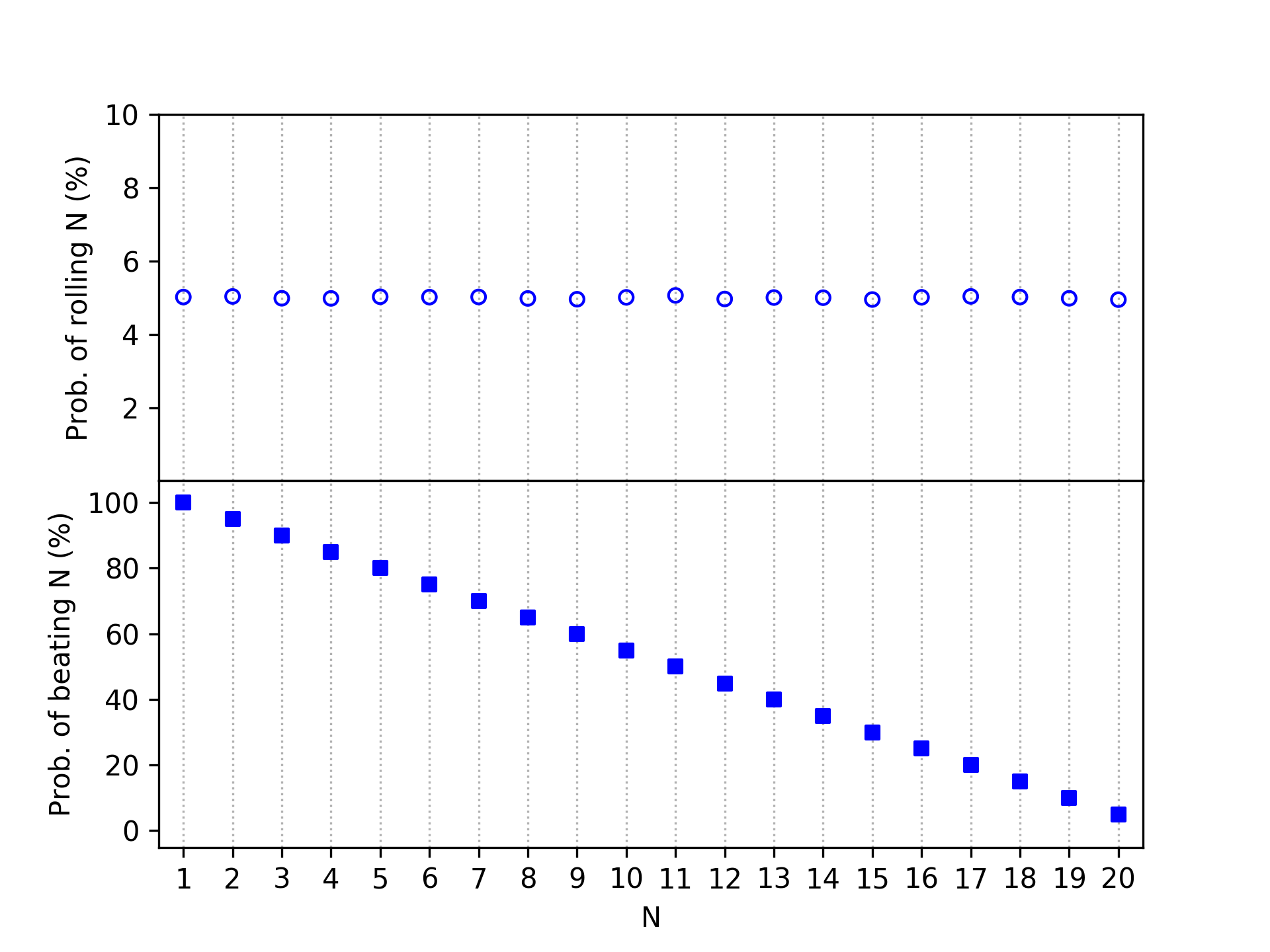

The easiest place to start is with the D20 itself. If we roll it 1,000,000 times, then we should expect each of the 20 possible values to come up about equally often. That is exactly what is shown in the top panel of the figure below. Each blue dot is the probability (y-axis) of rolling each specific number \( N \) on the D20 (x-axis). The bottom panel is also a probability plot, but this time showing the chances of beating (rolling equal or greater to) any given \( N \). Unsurprisingly, beating a lower roll is more likely than beating a higher one.

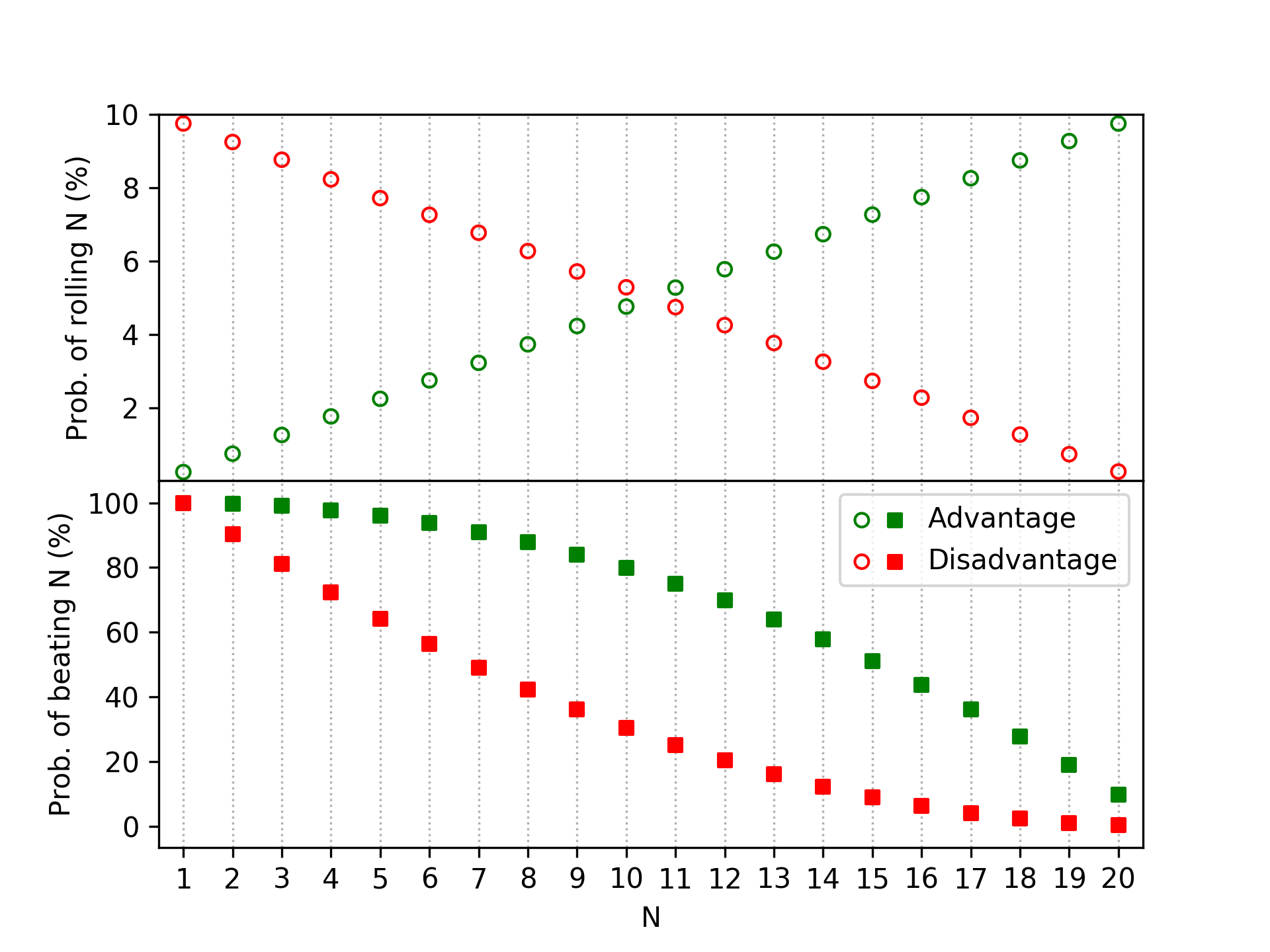

Adding advantage and disadvantage is straightforward enough. We tell the computer to roll two dice, and then pick the higher (or lower) one. And then do that 1,000,000 times. The figure below is analogous to the previous one: the top panel shows the probabilities for individual results using advantage (green) and disadvantage (red). On the bottom panel, we see just how much of a benefit rolling with advantage provides as opposed to rolling with disadvantage. Even beating a modest target roll like \( N = 10\) is about three times more likely with advantage than with disadvantage.

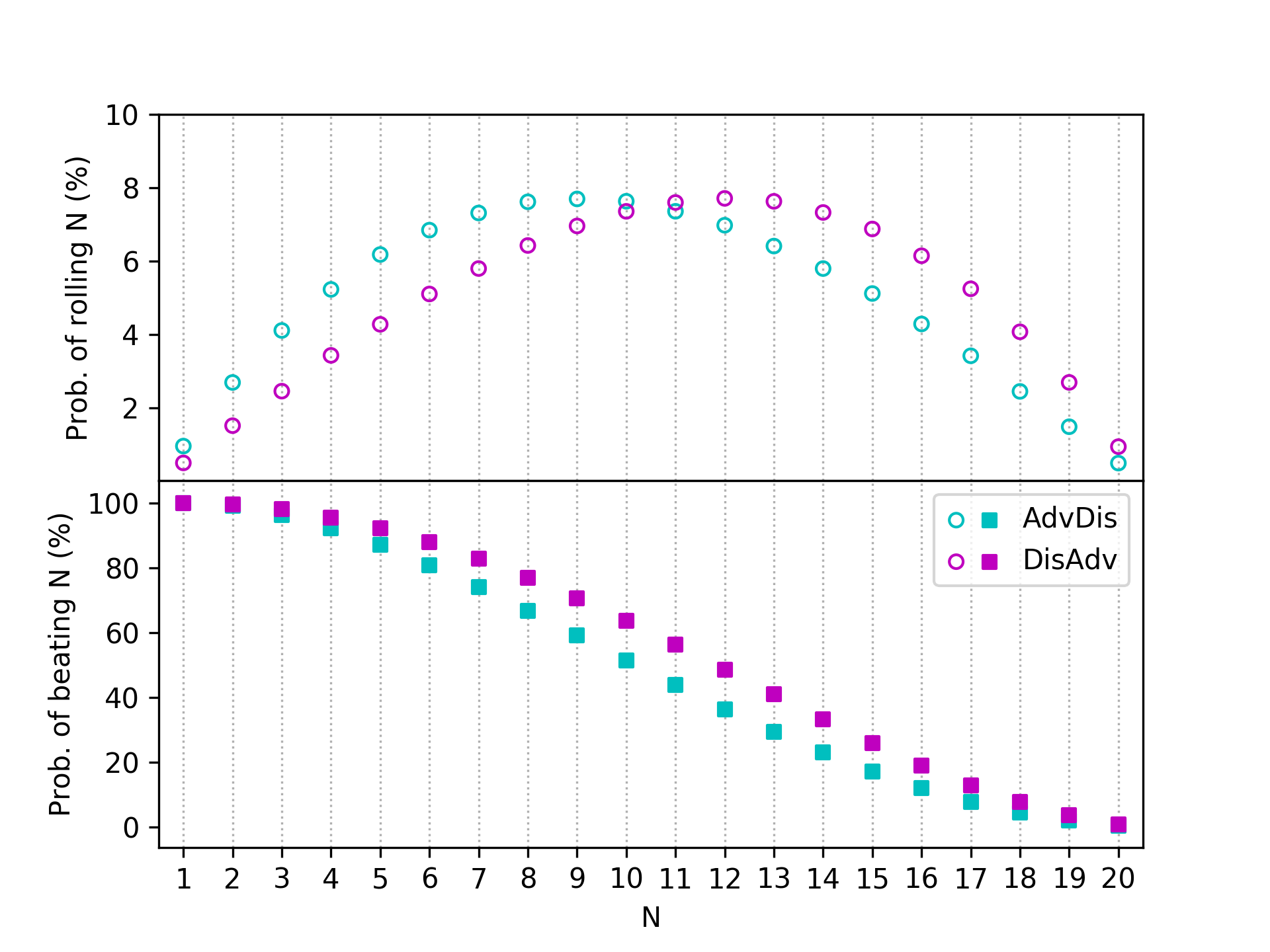

Now we get to the whole point of this exercise: advantage of disadvantage (which I will abbreviate as AdvDis) and disadvantage of advantage (DisAdv). Again, we take the approach of trying each of them 1,000,000 times. Intuitively I expect that DisAdv is superior because one takes advantage twice and disadvantage once (and this is vice versa for AdvDis). The results bear it out. The riddle asks for the expected roll values, which we get by taking the arithmetic mean of all 1,000,000 trials. This yields 9.83 for AdvDis and 11.17 for DisAdv. The expected roll for a normal D20 is 10.5, so in this sense DisAdv is superior.

The plot below shows the full probability distributions. The DisAdv (purple) probabilities are shifted slightly higher along the \( N \) axis than the AdvDis (cyan). For both, the values are peaked towards the middle, with probability of very low or very high rolls diminished. This makes sense, as extreme rolls are unlikely to make it through a few phases of maximizing/minimizing. The difference between the two cases is not very large

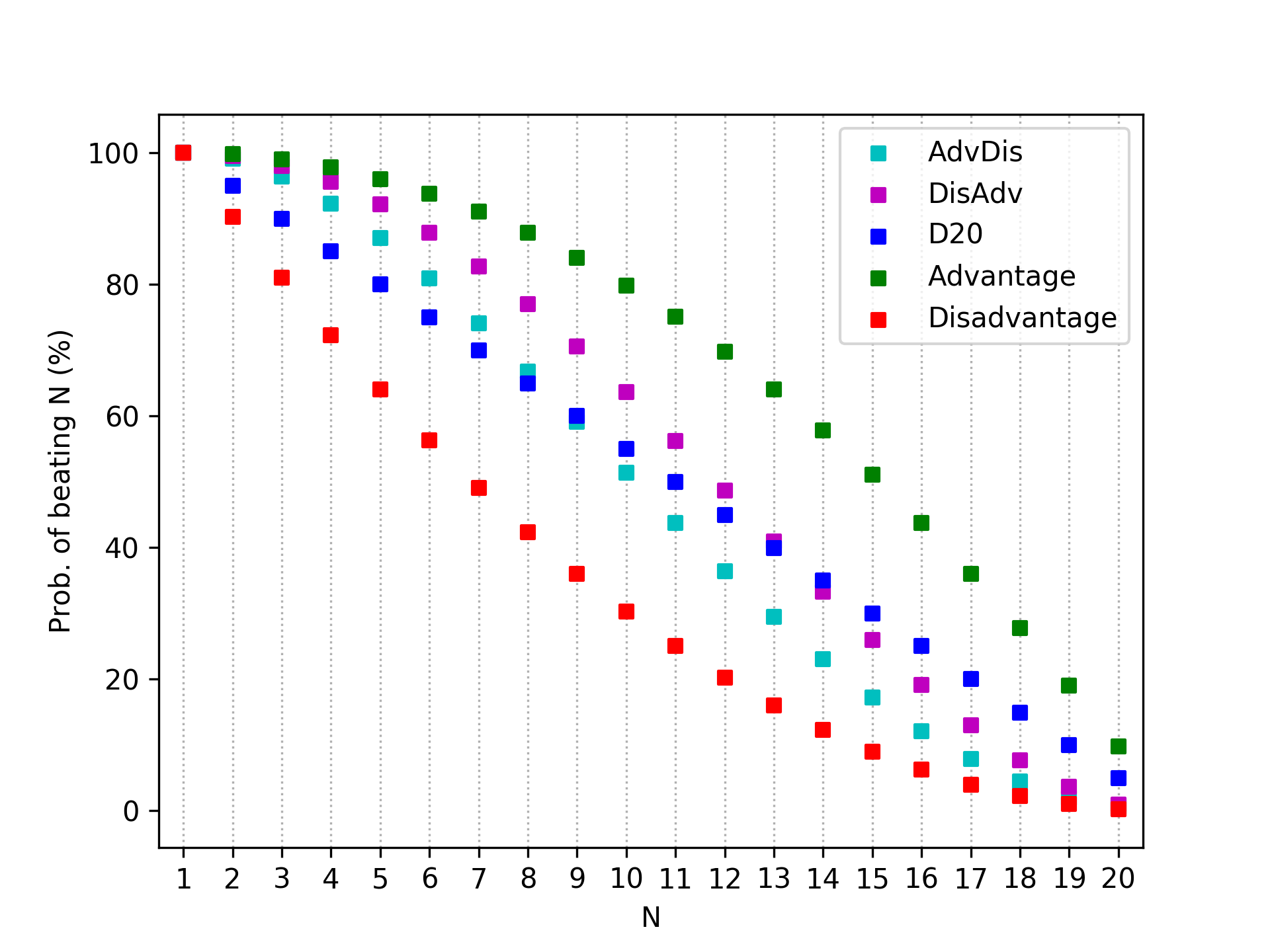

To answer the extra credit portion of the riddle, we need to figure out when rolling a D20, DisAdv, or AdvDis is a better option. The plot below shows the probability of beating \( N \) for all five of the different scenarios we have considered.

Obviously, pure advantage and pure disadvantage are the best and worst, respectively, and are plotted for the sake of comparison. Like I said, we care about D20, DisAdv, and AdvDis. For the lowest rolls, DisAdv is the best approach, followed by AdvDis and D20. At \( N = 9\), D20 and AdvDis switch places. Then, for a target number at 13 or above, rolling a normal D20 gives the best chance to succeed, followed by DisAdv and then AdvDis. So although DisAdv has the highest expected roll, if you are trying to beat a high target number then the D20 is the superior option.

In the end, of course, you just end up doing whatever the DM says anyways.

Technical Details

This was straigthforward from a technical perspective. I wrote a simple Python class to handle all the different rolling varieties, and used the standard randint function. The code can be found here. Histogramming is somewhat of a pain using pyplot, though.

Of course, the downside of this approach is that it is inexact. The uncertainty is purely statistical, and can be quantified by \( 1/\sqrt{T} \) where \( T \) is the number of trials. With \( T = 1000000 \), the uncertainty is 0.1%. I can live with that.

For the mathematically exact solution, check out all-time Riddler great Laurent Lessard’s solution.